subscribe via RSS

Benchmarking PostgreSQL's SELECT Query Planning and Performance on Columns Aggregates

Executing a single query doesn’t always literally mean executing exactly ONE query. Sometimes PostgreSQL (like any other relation database) will have to extract parts of your query (subqueries) and re-execute it as many times as needed to generate the results you are expecting it to generate. This article shows how N+1 issues can also happen without an explicit intent to produce them.

Introduction to the problem

Computing aggregated columns is a common task, sometimes requiring the relational engine to go through more than one table: counting comments on blog posts, counting favorites on tweets, …

This task can be done in many ways, here are the first three that come to my mind:

- Using multiple queries

# Query all `Posts`

SELECT * from posts

# For each `Post`, query its `Comments` count

SELECT count(1) from comments where post_id = ?- Using a

JOIN

SELECT

posts.id,

count(1)

FROM posts

LEFT OUTER JOIN comments

ON posts.id = comments.post_id

GROUP BY posts.id- Substitute a column for a subquery

SELECT

posts.id,

(SELECT count(1)

FROM comments

WHERE comments.post_id = post.id) comments_counts

FROM postsWhile many developers now about the performance implications and issues of solution #1 (the N+1 queries it will generate — where N is the number of blog posts), it isn’t obvious what would be the difference between solution 2 and 3, especially when it comes to dealing with large datasets.

Running the benchmarks

Let’s take those two implementations (the one based on JOINs and the one using a subquery), and analyze the difference1.

For that purpose, let’s use EXPLAIN ANALYZE on both of them. We will use the LIMIT clause and iteratively restrict the dataset to see the complexity trend: are we going to observe a logarithmic growth? linear growth? constant time?

Using JOINs

Let’s first analyze the JOIN strategy:

explain analyze select p.id, count(c.post_id) from posts p left outer join comments c on p.id = c.post_id group by 1; — no limit yet

UERY PLAN

—————————

HashAggregate (cost=1768.05..1773.05 rows=500 width=4) (actual time=28.696..28.749 rows=500 loops=1)

Group Key: p.id

-> Hash Right Join (cost=14.25..1501.65 rows=53280 width=4) (actual time=0.207..18.019 rows=49901 loops=1)

Hash Cond: (c.post_id = p.id)

-> Seq Scan on comments c (cost=0.00..754.80 rows=53280 width=4) (actual time=0.007..4.832 rows=50000 loops=1)

-> Hash (cost=8.00..8.00 rows=500 width=4) (actual time=0.192..0.192 rows=500 loops=1)

Buckets: 1024 Batches: 1 Memory Usage: 18kB

-> Seq Scan on posts p (cost=0.00..8.00 rows=500 width=4) (actual time=0.012..0.097 rows=500 loops=1)

Planning time: 0.121 ms

Execution time: 28.825 msThe plan for that query is pretty straightforward:

- The planner first executes a sequential scan (i.e.: reads all the records out of the

poststable, which is the smallest table) and stores rows with the sameidin the same bucket (each post has a unique id though, so this doesn’t seem really meaningful in our case, but this is a performance trick to avoid hashing the largest table and overusing the memory). Accessing posts later on, in memory, will be achieved in constant time2 - Then it will scan all the

comments, and iteratively merge the two datasets using the pre-computed hash key (post_id) and theHash Right Joinfunction. At this point, a dataset ofN * Mrecords (Nfor the number of posts,Mfor the number of comments) could exist. However, the hash algorithm we’re using don’t require to have the whole dataset in memory and only buffers the aggregated results - Finally, we aggregate this dataset using the

HashAggregatefunction.

Using JOIN makes use of HashAggregate, which is very efficient (and if both tables comes already sorted by the id/post_id columns, the planner will decide to use the GroupAggregate function and the query will be even more efficient).

This solution is pretty straightforward but having to use (and write) a combination of a LEFT OUTER JOIN and a GROUP BY clause can sometimes be scary for those unwilling to deal with any kind of SQL statements.

ORMs don’t particularly make this easy on developers. As an example, let’s take a look at Ruby on Rails’s Active Record’s DSL (Domain Specific Language):

Post.

joins(“left outer join comments on posts.id = comments.post_id”).

select(“posts.id, count(1) comments_count”).

group_by(“1”)Some people will probably want to switch to using raw SQL (with ActiveRecord::Base.connection#execute) but this limitation is inherent to using an ORM.

Using a subquery

Now onto the subquery. The solution looks seducing at first sight: a query nested within another: no grouping, no joining, just a simple WHERE clause from the parent plan (not sure about the wording here).

# explain analyze select p.id, (select count(1) from comments c where c.post_id = p.id) from posts p;

Seq Scan on posts p (cost=0.00..444345.50 rows=500 width=4) (actual time=5.110..1906.266 rows=500 loops=1)

SubPlan 1

-> Aggregate (cost=888.66..888.67 rows=1 width=0) (actual time=3.810..3.810 rows=1 loops=500)

-> Seq Scan on comments c (cost=0.00..888.00 rows=266 width=0) (actual time=0.029..3.793 rows=100 loops=500)

Filter: (post_id = p.id)

Rows Removed by Filter: 49900

Planning time: 0.100 ms

Execution time: 1906.397 msBefore even trying to decipher the plan, let’s compare our Execution time: 1,906 ms vs 28 ms. It’s a 6,600% increase…

The plan is now very different:

- A sequential scan is done on the

poststable. For each of these rows, a subplanSubPlan 1(i.e.: another query) is going to be executed. SubPlan 1is defined as:

2.1. It is going to be executed a certain number of time: this is the loops value. We can read 71, which matches the exact number of posts from our posts table: this plan will be executed 71 times

2.2. Given a post’s id, a sequential scan will be executed on the comments table

2.3. Once all the comments matching the post’s id have been retrieved, the result set is aggregated using the Aggregate function

SubPlan 1is executed and inserted in the row’s columns.

What the planner unveiled was a N+1 type of issue: given N records in a posts table, we will have as many subplans (or subqueries) as post records.

Using ActiveRecord will require developers to write some SQL, here are two ways of achieving the same result:

With nested SQL

Post.

select(“id,

(select count(1)

from comments c

where c.post_id = posts.id) comments_count”)With AR’s underlying Arel “relation engine”

subquery = Negotiation.

select(

Arel::Nodes::NamedFunction.new(“count”,

[Negotiation.arel_table[:id]])).

where(

Negotiation.

arel_table[:budget_id].

eq(Budget.arel_table[:id])).

to_sql # not calling #to_sql will execute the query

Budget.

select(“id, (#{subquery})”)Not really readable, the implicit (and hidden to the unwary) N+1 issue of that strategy makes its inefficient and potentially harmful.

Some figures

Let’s now test the performance of those queries on the same dataset. We’ll gradually increment the number of records to consider to observe the execution time growth.

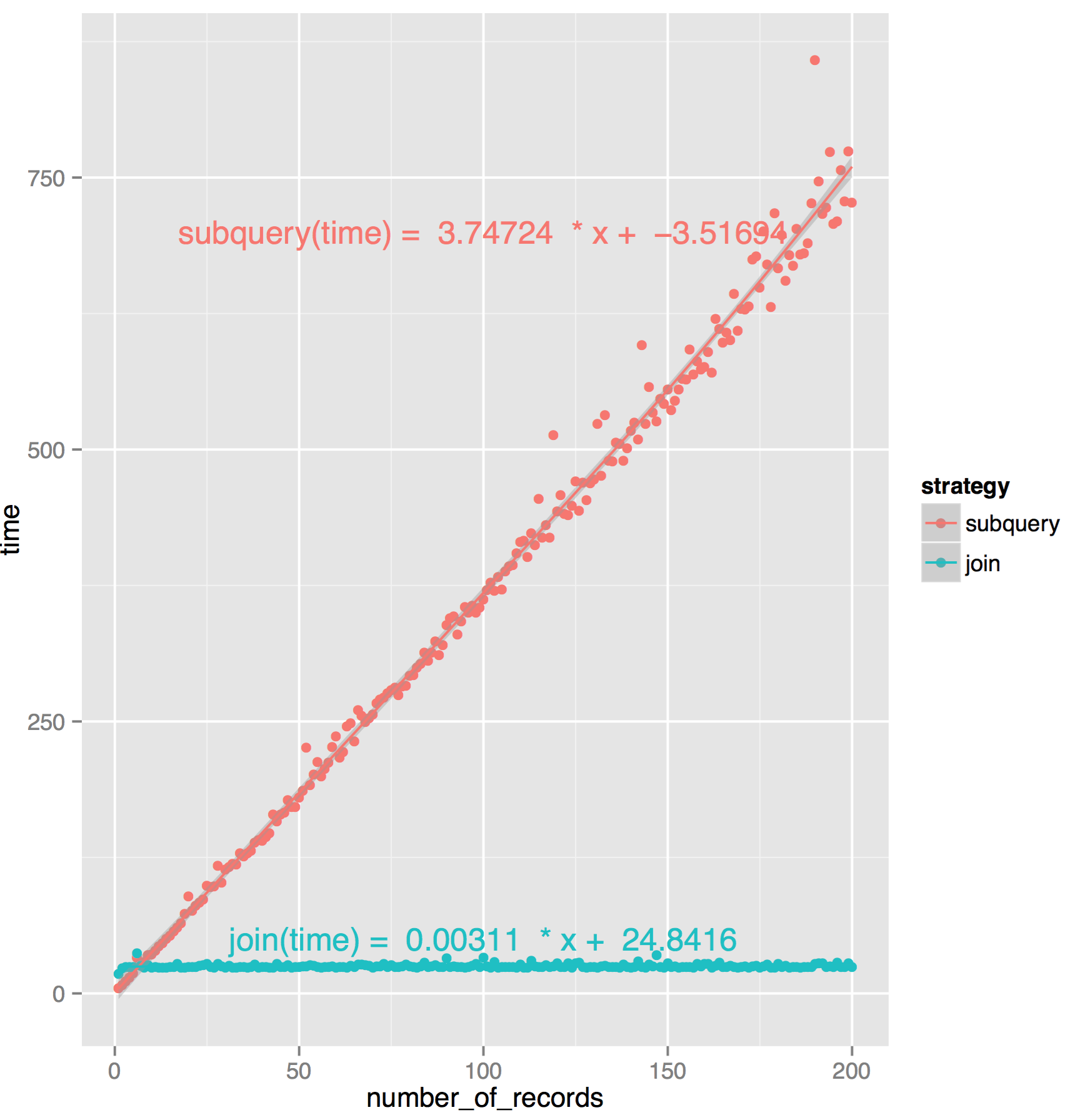

Applying a simple linear regression on the datasets, here are the two formulas that defines our two strategies’ performances:

- subquery(time) = 3.74724 × number of records + −3.51694

- join(time) = 0.00311 × number of records + 24.8416

| Number of records | Subquery Execution time (Estimated) |

`JOIN` Execution time (Estimated) |

Observation | JOIN faster than Subquery? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ± 0.23 ms | ± 24.84 ms | Extrapolated & Observed on the graph | No — 100 times slower |

| 200 | ± 746 ms | ± 25 ms | Extrapolated & Observed on the graph | Yes — 29 times faster |

| 1000 | ± 3,7 seconds | 28 ms | Extrapolated | Yes — 133 times faster |

| 10,000 | ± 37 seconds | ± 56 ms | Extrapolated | Yes — 669 times faster |

| 100,000 | ± 1 hour | ± 336 ms | Extrapolated | Yes — 1115 times faster |

Conclusion

Most developers working with ORMs are aware of the limitations of their tools and how to avoid N+1 in their code (using eager-loading strategies for example).

But N+1 doesn’t only mean “sending N+1 statements to the database”, sometimes this single statement can turn into an unbelievably time-consuming statement with thousands of subplans (subqueries).

Active Record has an #explain method that can help developers understanding the generate SQL.

As an exercise to the reader, I’d suggest comparing query plans when the number of posts and the number of comments differ. For example, here’s the query plan for 50k posts, and only 5k comments:

GroupAggregate (cost=380.61..2636.48 rows=50000 width=32) (actual time=1.985..36.122 rows=50000 loops=1)

Group Key: p.id

-> Merge Left Join (cost=380.61..1886.48 rows=50000 width=32) (actual time=1.964..20.567 rows=54491 loops=1)

Merge Cond: (p.id = c.post_id)

-> Index Only Scan using unique_post on posts p (cost=0.29..1306.29 rows=50000 width=4) (actual time=0.013..10.559 rows=50000 loops=1)

Heap Fetches: 0

-> Sort (cost=380.19..392.69 rows=5000 width=32) (actual time=1.933..2.283 rows=5000 loops=1)

Sort Key: c.post_id

Sort Method: quicksort Memory: 583kB

-> Seq Scan on comments c (cost=0.00..73.00 rows=5000 width=32) (actual time=0.010..0.763 rows=5000 loops=1)

Planning time: 0.810 ms

Execution time: 38.813 msAs you can see, not only it will use the unique index on the posts table, but also use a GroupAggregate given the comments are being sorted in memory.

Also, the planner can decide to build totally different plans based on the statistics it’s computed on the database, so please analyze frequently.

1: *A GitHub’s repository is available with the source code so that the results are reproducible. Please feel free to contact me if some of the numbers don’t feel right, I will keep the repository updated**.

2: Complexity is O(log1024(N)) (N being the number of posts records) as the planner created 1024 buckets. With a table containing billions of billons (1018) of records, the complexity is O(6), simplified as O(1).